Bolle Willum Luxdorph, who lived from 1716-1788, was the first Dane known to have studied the phenomenon of old age. Luxdorph was a high-ranking Danish civil servant, leader of the Danish Chancellery as well as a scholar and poet. In the last years of his life Bolle Luxdorph created a collection of pictures of long-livers. A fact which has been known from Bolle Luxdorph's diary, which was published in the early part of this century (Luxdorph 1915-30). In 1988 some drawings in the collections of the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle were identified as originals from Luxdorph's collection, and a reconstruction of a small part of the collection of drawings was published by Thorkild Kjærgaard in the Annual Report of the Carlsberg Foundation (Kjærgaard 1990).

The exact date at which Luxdorph began taking an interest in the phenomenon of old age is not known, but it must have happened some time in the late 1770s. At this point, anyway, Luxdorph began systematically collecting data concerning very old people i.e. persons who had reached the age of 80 and over. Luxdorph, who was eminently proficient in classical as well as modern languages, ploughed through literature from throughout the ages, looking for information about persons who had reached extreme old age. At the same time he began an extensive correspondence with members of the Danish and Norwegian clergy, asking them to search the church registers of their parishes in order to find information about centenarians, just as he kept an eye on the newspapers and periodicals of his time looking for information concerning long-livers (Kjærgaard 1995).

The first result of Luxdorph's interest in the phenomenon of old age was a manuscript in Latin: Catalogus longævorum from 1780. This catalogue was never printed, but survives as a beautiful manuscript in the Royal Library of Copenhagen. Catalogus longævorum contains concise information on several hundred persons, ordered alphabetically and mainly from antiquity. It is quite obvious from the empty spaces left in the manuscript, that Luxdorph intended to have it illustrated. This idea was never realised, however, though a few pen-and-ink drawings survive. These had for the main part been copied from Jacob Gronov's Thesaurus Graecarum antiquitatum published in 12 volumes in Leyden 1697-1702. After 1780 Luxdorph used the blank pages of Catalogus longævorum to write notes about long-livers which he had come across, mainly in the periodical literature of his time.

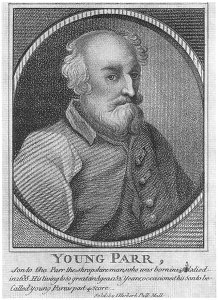

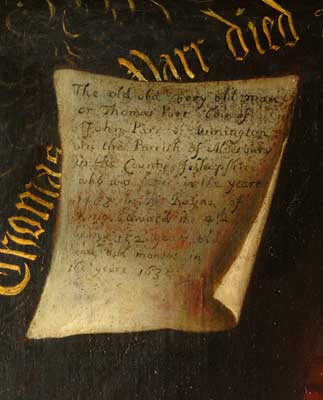

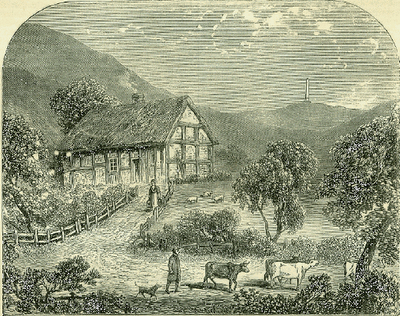

It proved much easier to come by pictures of Luxdorph's contemporaries. Even before the completion of Catalogus longævorum, Luxdorph was busy building up a collection of pictures of old people, mainly from his own time and the recent past. Existing prints depicting old people were procured, and when no picture was available, Luxdorph went through great lengths to have one made. Many of the clergymen with whom Luxdorph corresponded were requested to procure pictures of the old persons whom they had informed Luxdorph about.

In 1783 Luxdorph published a catalogue of his pictures of long-livers, a printed book of 36 pages: Index tabularum pictarum et cælatarum qvæ longævos representant (Catalogue of painted and engraved pictures representing long-livers). Important changes had taken place compared to Catalogus longævorum from 1780. Firstly the main emphasis now lay on Luxdorph's contemporaries or near-contemporaries. Secondly an important change had been made in the ordering of the material, the alphabetical ordering of Catalogus longævorum had been replaced by the - from a gerontological point of view more interesting - sociological-systematical principle of age. Each person in the gallery is carefully listed according to the number of years, months and days of his or her life, with the oldest person - the Hungarian Petracz Czartan - first.

Index tabularum was dedicated to Count Otto Thott, who was Luxdorph's political chief and himself an ardent book collector on a much grander scale than Luxdorph. Index tabularum was published on the occasion of Thott's 80th anniversary on October 15th 1783, the pictures of Otto Thott - youngest of the old - concluding the book. Bolle Luxdorph probably had his inspiration for this rather elaborate birthday present from the story of André Hercules Cardinal de Fleury about whom he writes that Barjac, the valet of cardinal Fleury, some time before the death of Fleury arranged for Fleury to have Twelfth-night dinner with twelve others who were all older than him, thus obliging Fleury as the youngest to "tirer le gateau" (draw the cake)(Luxdorph 1783 p. 14).(1)

The 1783 catalogue lists 271 pictures representing 254 persons, since some of the persons were represented by more than one picture. For the remaining five years of his life Luxdorph continued collecting pictures of long-livers, and it is known that he intended to publish an extended edition of his 1783 catalogue and that a manuscript existed (Luxdorph 1915-30 p. 421 and Junge 1789 II Icones Longævorum p. 79).

On August 13th 1788, Luxdorph died 72 years old. In his will he had left detailed instructions regarding his collections, and the catalogue which was to be made of them for the auction after his death. About his pictures of longævi Luxdorph states: "That all longævi with their age and which of them are but drawings be specified" (Luxdorph 1915-30 II p.421).(2)

Luxdorph's instructions were carried out in the catalogue for the auction in 1789, called Bibliotheca Luxdorphiana, which was compiled by Joachim Junge, who had worked with Luxdorph in his library since 1784. Luxdorph's pictures of long-livers are listed in a separate part of Bibliotheca Luxdorphiana called Icones longævorum. In this list - which constitutes the basis of the reconstruction of Luxdorph's picture gallery - the number of pictures in Luxdorph's collection had grown to 728 representing 515 persons. Of these pictures 78 are drawings, and 650 are prints. The ordering of the material in Icones longævorum is in principle the same as the ordering in Index tabularum, there is, however, one small difference. The ages of the persons in Icones longævorum are given in years only, and generally as the number of years commenced, so that "m. æt. 95" means died in his 95th year, and thus the person in question may have died at the age of 94. This means that in some cases there is a one-year discrepancy between the ages given in Index tabularum and those given in Icones longævorum. At the auction in the autumn of 1789 this unique collection was sold as one lot to an unknown buyer, and was then lost sight of for 200 years.

Read more